Well, the day came, and it went. The historic UFC 157 was a success and, while it didn’t possess the greatest card of fights, the event delivered what was promised. There were plenty of exciting moments: Urijah Faber clambered onto Ivan Menjivar’s back and sunk in a thrilling rear naked choke while the Salvadoran-Canadian stood helpless. And apparently unafraid of inviting even further comparison to the California Kid, Liz Carmouche attempted the same submission against Ronda Rousey, but ultimately failed to prevent the Rowdy One from adding yet another arm to her collection. And, as I predicted in last week’s article, Lyoto Machida walked away with the decision win over Dan Henderson.

The decision didn’t come easily, and I mentioned last week that Lyoto would have some struggles in this bout. The nature of the struggle, however, was not one that I predicted. Yes, Dan was a game opponent, and he remained a threat until the very last bell. But it wasn’t Dan that gave Lyoto trouble; it was the judges. Shockingly, the first score announced after the fight was in favor of Dan Henderson, 29 points to 28.

Lyoto’s face at the sound of that announcement mirrored my own. “What?” I thought. “How could anyone have scored that bout with two rounds in Dan’s favor?” I began having vivid flashbacks of Henderson vs. Ninja Rua. But my dear friend Machida and I were both relieved to hear that the next two judges had given Lyoto two of the rounds, securing him the win. Granted, I was convinced that Lyoto had won every round. But I wasn’t about to complain about the victory being given to the right person.

Looking it up later that night, I saw that this man was one of the judges:

…and immediately knew who to blame the pro-Henderson score on. I happily attributed the bizarre scores to the fifteen minute smoke break that Mr. Peoples undoubtedly took during the fight, and called it a day.

…and immediately knew who to blame the pro-Henderson score on. I happily attributed the bizarre scores to the fifteen minute smoke break that Mr. Peoples undoubtedly took during the fight, and called it a day.

So imagine my surprise when I checked the message boards in the morning, and saw that a great number of people had scored the fight similarly. Machida was accused of running, being overly tentative, and failing to engage. I was puzzled, because the fight I watched gave me a different impression. The fight I watched looked an awful lot like, well… a Machida fight. I had expected no different. But lots of folks were disappointed with the Dragon’s performance, so I decided to review the fight and see if my initial assessment was wrong.

Well, people, I watched it again. And a third time, and a fourth. And, fortunately for me, I don’t feel there is any cause for me to rescind my initial opinion. I can go on being unrepentantly proud of my fight prediction skills, because that fight was Machida’s all the way. Furthermore, I still think there’s a strong case for giving him all three rounds. Let’s break down why.

(Note: This will not be a “Winning the Round” style of breakdown, despite the decision result. I just can’t limit myself to three techniques here. I hope you’re down for a long one. Grab a beer or fix some coffee–I’ll wait.)

ROUND ONE

Immediately after the fight began, Dan Henderson made his strategy clear. Machida struggled with defending low kicks against Mauricio Rua, and clearly Henderson’s camp thought this would be useful. Unfortunately, Hendo isn’t close to the kicker that Shogun was, and this was evident as he threw the first of many awkward, stiff-hipped low kicks.

There was some reasoning behind this. It’s well known that Dan loves to throw the lead inside leg kick as set up for his right hand. And if you didn’t know about it before the fight, Mike Goldberg saw fit to inform the audience appoximately seventeen times per round that it is, in fact, Dan’s favorite set up. But not everything Goldie talks about is stupid. It’s a smart combo. The opponent is immobilized by the kick, and the simple action of setting the kicking leg down leads very smoothly into the massive slobberknockin’ overhand that Dan favors. It’s worked well many times in the past.

There was some reasoning behind this. It’s well known that Dan loves to throw the lead inside leg kick as set up for his right hand. And if you didn’t know about it before the fight, Mike Goldberg saw fit to inform the audience appoximately seventeen times per round that it is, in fact, Dan’s favorite set up. But not everything Goldie talks about is stupid. It’s a smart combo. The opponent is immobilized by the kick, and the simple action of setting the kicking leg down leads very smoothly into the massive slobberknockin’ overhand that Dan favors. It’s worked well many times in the past.

But Lyoto is (usually) a southpaw. You could see Dan hungrily leap for the lead leg kick whenever Machida went orthodox in the first round, but Machida was wise to it and danced out of range, and otherwise the classic H-Bomb set up wasn’t an option. So Dan was relegated to throwing arthritic rear leg kicks instead. These kicks account for the relatively high number of strikes listed under Dan’s name in the CompuStrike summary, but they certainly didn’t count for much in the fight, and they’re no reason to give Henderson the first round.

But Lyoto is (usually) a southpaw. You could see Dan hungrily leap for the lead leg kick whenever Machida went orthodox in the first round, but Machida was wise to it and danced out of range, and otherwise the classic H-Bomb set up wasn’t an option. So Dan was relegated to throwing arthritic rear leg kicks instead. These kicks account for the relatively high number of strikes listed under Dan’s name in the CompuStrike summary, but they certainly didn’t count for much in the fight, and they’re no reason to give Henderson the first round.

A good jab would have really helped Dan here. If Hendo had prepared himself to step in behind a jab, he might have actually been able to pin Lyoto down or catch him mid-counter. Simple boxing suits Dan much better than the “Muay Thai” he was trying to bust out throughout this fight. And whereas a simple 1-2 is far from a guarantee against Machida, Dan’s kicks couldn’t have been hurting the Dragon any more than they were hurting his own toes. Very ineffective.

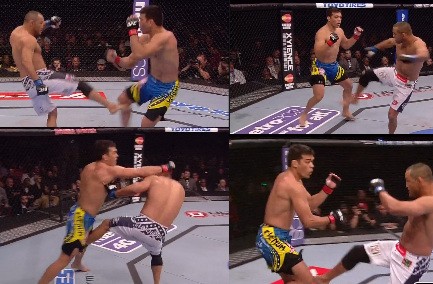

Machida, on the other hand, spent the first portion of the round just watching Henderson. He’s well known for his feinting movements, including the lady-killing rear-leg hip twist that he’s so fond of, and the Machida dance was on full display tonight. For over two full minutes the Brazilian read Henderson’s reactions carefully and avoided his strikes, only attacking himself with a handful of front kicks to the body. And then:

Lyoto unleashes his legendary straight left. This punch went largely unnoticed because of the camera angle and Machida’s blinding speed, but it lands solidly. As proof, Dan was wearing a shiny new contusion under his right eye for the rest of the fight. Notice how Lyoto intercepts Henderson–his left hand connects while Hendo is still in the process of loading up his right– and then immediately takes the angle and puts himself in a position to defend. Dan bullrushed him after this, but to no avail.

Lyoto unleashes his legendary straight left. This punch went largely unnoticed because of the camera angle and Machida’s blinding speed, but it lands solidly. As proof, Dan was wearing a shiny new contusion under his right eye for the rest of the fight. Notice how Lyoto intercepts Henderson–his left hand connects while Hendo is still in the process of loading up his right– and then immediately takes the angle and puts himself in a position to defend. Dan bullrushed him after this, but to no avail.

This little encounter proved to be the model for the rest of the night’s exchanges. Dan would jump in loading up the big punch, and Lyoto would intercept. Moments after this straight left, a hard left body kick interrupted another of Dan’s awkward kicks, followed by a pair of punches. Seconds later Dan lunged forward into the first knee of the night, which didn’t land perfectly, but certainly stopped the All-American’s momentum well enough.

And then Dan’s only real success in the entire fight.

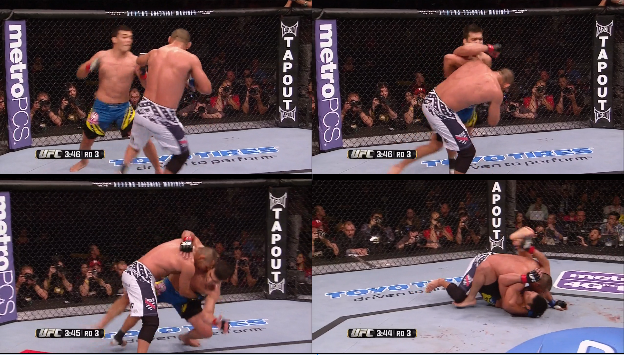

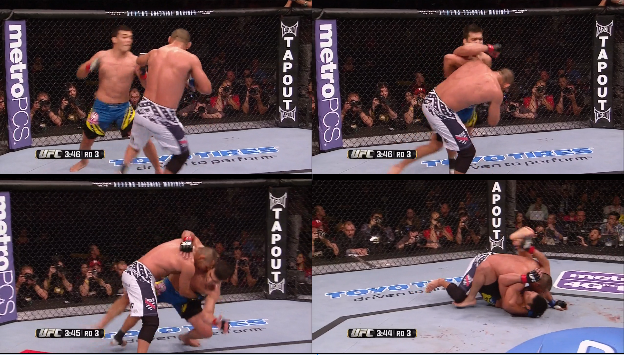

Blammo! Lyoto takes the H-bomb to the chin, and another one to follow up. I’d like to say that I was impressed with Dan’s quickness on these shots, but at the time I was shitting myself. I was sure that Hendo had just knocked out Lyoto Machida. But the Brazilian ate the punches like Acai and, tying up with ten seconds remaining, sealed the round for good with a beautiful takedown.

Blammo! Lyoto takes the H-bomb to the chin, and another one to follow up. I’d like to say that I was impressed with Dan’s quickness on these shots, but at the time I was shitting myself. I was sure that Hendo had just knocked out Lyoto Machida. But the Brazilian ate the punches like Acai and, tying up with ten seconds remaining, sealed the round for good with a beautiful takedown.

Machida has a very strong underhook, and he walks slowly backwards, feeling for Henderson’s weight to shift. As soon as he feels Dan step and put his weight on his left leg, Machida kicks out the right leg and twists the Greco-Roman wrestler down to the mat. Seconds left and Machida connects with a hard left hand and a forearm to the temple before walking away, mouthing the Portuguese for “like a boss” to himself. Meanwhile, Dan staggers back to his corner breathing hard, undoubtedly haunted by the ghost of Thiago Silva, whose fate he almost just met.

ROUND TWO

Round two showed us an increasingly frustrated Dan Henderson. Aside from those awkward kicks and one solid left hook, Henderson still finds it nearly impossible to lay a hand on the dragon. But far too many people are making the mistake of blaming this on Henderson. No, Dan did not present a wide array of attacks. He was pretty much always looking for that right hand, and his assault was further hampered by his reluctance to commit himself to that one attack the way he might have against a slower striker like Shogun. Granted, that conservative attitude might have saved Dan from suffering his first knockout at the precise hands of Machida.

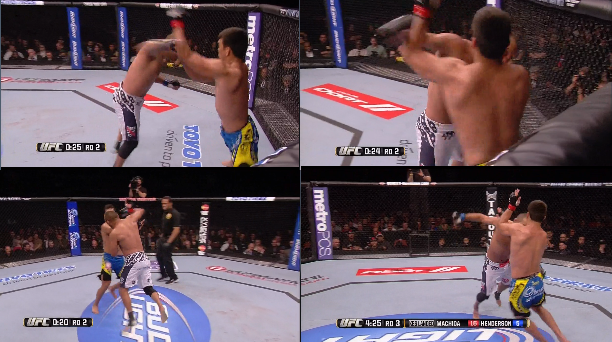

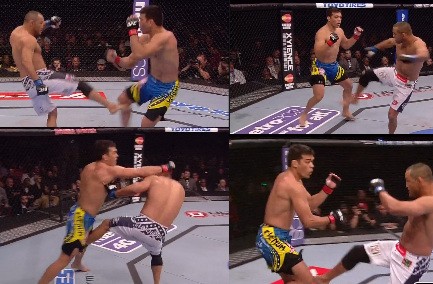

Regardless, Dan’s frequent overhands couldn’t find their mark because of an adaptation that Machida has made recently to his game, one that I, for one, am very glad to see. Dan very well might have knocked out the Machida that fought Shogun, or even the one that was knocked down by Jon Jones just over a year ago. But not this Machida. Check out these stills:

Here we have what I believe is called Chudan Haishu Uke, or a high back hand block. It’s basically a variant of one of the first techniques you would learn as a six year old at a Karate dojo. And wouldn’t you know–the damn thing works! The Machida who used to backpedal away from strikes with his hands down and his chin in the air is no more! Well, he still carries his chin high, true. And yes, he still backpedals an awful lot. But by gum, he blocks when he does it now!

Here we have what I believe is called Chudan Haishu Uke, or a high back hand block. It’s basically a variant of one of the first techniques you would learn as a six year old at a Karate dojo. And wouldn’t you know–the damn thing works! The Machida who used to backpedal away from strikes with his hands down and his chin in the air is no more! Well, he still carries his chin high, true. And yes, he still backpedals an awful lot. But by gum, he blocks when he does it now!

Would this sort of defense fly in high level boxing or kickboxing? Probably not. But Lyoto Machida proves once again that the simple self-defense minded techniques of Karate can be very effective in MMA.

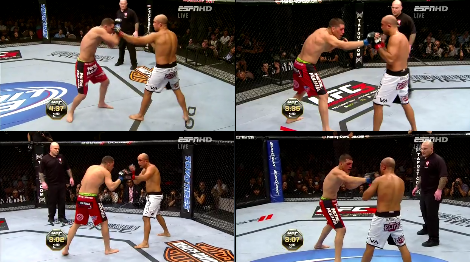

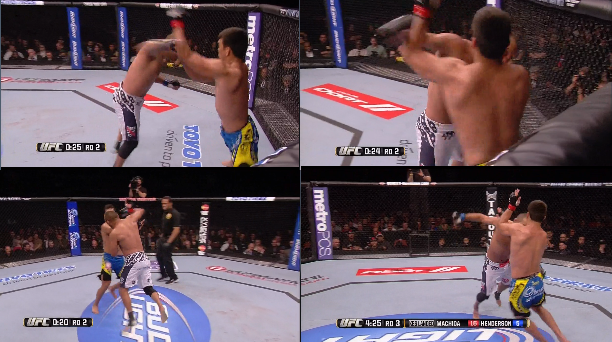

Aside from defending, the Dragon was also able to land a front kick to the face followed by a series of punches, a spinning back kick at the end of the round, and a whole slew of vicious knees to the body. But the one attack that stood out in the second frame was this tremendous body kick.

Dan wants to throw a right hand. It would be nice for this one to catch Machida off-guard, but he’s Dan Henderson, damn it, so he telegraphs the shit out of it. Machida, of course, sees it coming, and immediately hop-steps into a huge left body kick. Notice how his head pulls back and slightly off-center when he kicks. Also, I don’t know if those two days in the company of Melvin Manhoef had any real effect, but this is much more of a powerful Thai-style kick than we’re used to seeing from Lyoto. He catches Henderson right across the liver with his shinbone while the American is reaching with a pawing jab, still cocking back his right hand. And the kick is so powerful, and catches Henderson at just the right moment, that it rips Hendo clean off his feet. Dan sprang right back up after this blow landed, and seemed determined to teach Tito Ortiz a thing or two about absorbing body shots, but the kick was spectacular nonetheless.

ROUND THREE

Final round, and Dan is getting frustrated. He threw up his hands in exasperation before walking back to his corner after the second round, and he comes out in the third still breathing heavily. Machida blasts him with a cracking bodykick, and then decides to play around with some sort of Zab Judah-esque 52 Blocks hand movement. You could call it feinting, but I call it too much time spent hanging out with Anderson Silva.

After another right hand is blocked (kiyah!), Dan tries a new technique. Wait, no. He tries an inside leg kick. Except this time it has a visible effect.

He catches Lyoto while the Brazilian is trying to counter him, and knocks his leg out from under him. The Karateka falls to the canvas with Dan inside his guard. This, right here, is the only justifiable reason I see to give Hendo a round. He controls Machida from the top and tries to land elbows to the body and leg, but Lyoto’s closed guard is very strong. I was a bit disappointed by this at first. I was hoping to see some submissions or sweeps from Machida. At one point he could have taken Dan’s back, but he seemed content to protect himself and ride out Dan’s assault. But then he showed us that there are some facets to his ground game with a slick hip bump sweep. He couldn’t put Dan in mount, but he managed to disengage and get back to his feet.

And, for those detractors of Machida’s evasive style, I would point to the final minutes of this fight as a counter. For the rest of the round, it’s Machida on the front foot and the gassed Dan Henderson retreating. The roles are reversed, except that Lyoto’s aggression is actually effective.

Lyoto first teaches Dan a lesson on throwing inside leg kicks with a vicious blow to the thigh. Soon after he throws the jumping front kick that he used against Couture, and follows it up with a blistering roundhouse kick. Both land directly on Dan Henderson’s granite chin, and he smiles at Lyoto. In response, Lyoto makes sure to do even more absurd hand movements for the rest of the round, including what appears to be the Lyoto Machida version of Nick Diaz’s favorite taunt.

Considering that Hendo was unable to do any considerable damage from his top position and spent the rest of the round retreating and defending without countering, there is still a very strong case for giving this round to Machida.

Throughout the fight, Machida landed the cleaner shots and avoided being hit himself, taking only two punches in the entire fight. Octagon control is a factor, but Lyoto displayed more of the coveted generalship than Dan throughout the bout. Remember, walking forward is not control. Allowing a guy to walk into your strikes while avoiding his is. Pat Barry recently said it best, and I’m paraphrasing: “Guy A is walking forward, Guy B is walking backward. If Guy B is landing more shots, then it’s time for Guy A to start running forward.” Simply walking into counters is not effective aggression.

So, Dan: I love you, buddy. But you knew coming into this what Machida was going to do. And Lyoto, despite all the detractors and booing goons in the crowd, I thought you did your work beautifully.

So. Who’s up for another try at the Machida Era?

‘Cause I sure as hell am.

Edit: For those who still have doubts about who won that fight, or those who love watching Machida work as much as I do, there is a lovely thread on the Sherdog forums with tons of .gifs from the fight. You can find that here.

Follow Connor on Twitter @ConnorRuebusch for blog updates, or if you prefer his writing in much, much smaller portions.

…and immediately knew who to blame the pro-Henderson score on. I happily attributed the bizarre scores to the fifteen minute smoke break that Mr. Peoples undoubtedly took during the fight, and called it a day.

…and immediately knew who to blame the pro-Henderson score on. I happily attributed the bizarre scores to the fifteen minute smoke break that Mr. Peoples undoubtedly took during the fight, and called it a day. There was some reasoning behind this. It’s well known that Dan loves to throw the lead inside leg kick as set up for his right hand. And if you didn’t know about it before the fight, Mike Goldberg saw fit to inform the audience appoximately seventeen times per round that it is, in fact, Dan’s favorite set up. But not everything Goldie talks about is stupid. It’s a smart combo. The opponent is immobilized by the kick, and the simple action of setting the kicking leg down leads very smoothly into the massive slobberknockin’ overhand that Dan favors. It’s worked well many times in the past.

There was some reasoning behind this. It’s well known that Dan loves to throw the lead inside leg kick as set up for his right hand. And if you didn’t know about it before the fight, Mike Goldberg saw fit to inform the audience appoximately seventeen times per round that it is, in fact, Dan’s favorite set up. But not everything Goldie talks about is stupid. It’s a smart combo. The opponent is immobilized by the kick, and the simple action of setting the kicking leg down leads very smoothly into the massive slobberknockin’ overhand that Dan favors. It’s worked well many times in the past. But Lyoto is (usually) a southpaw. You could see Dan hungrily leap for the lead leg kick whenever Machida went orthodox in the first round, but Machida was wise to it and danced out of range, and otherwise the classic H-Bomb set up wasn’t an option. So Dan was relegated to throwing arthritic rear leg kicks instead. These kicks account for the relatively high number of strikes listed under Dan’s name in the CompuStrike summary, but they certainly didn’t count for much in the fight, and they’re no reason to give Henderson the first round.

But Lyoto is (usually) a southpaw. You could see Dan hungrily leap for the lead leg kick whenever Machida went orthodox in the first round, but Machida was wise to it and danced out of range, and otherwise the classic H-Bomb set up wasn’t an option. So Dan was relegated to throwing arthritic rear leg kicks instead. These kicks account for the relatively high number of strikes listed under Dan’s name in the CompuStrike summary, but they certainly didn’t count for much in the fight, and they’re no reason to give Henderson the first round. Lyoto unleashes his legendary straight left. This punch went largely unnoticed because of the camera angle and Machida’s blinding speed, but it lands solidly. As proof, Dan was wearing a shiny new contusion under his right eye for the rest of the fight. Notice how Lyoto intercepts Henderson–his left hand connects while Hendo is still in the process of loading up his right– and then immediately takes the angle and puts himself in a position to defend. Dan bullrushed him after this, but to no avail.

Lyoto unleashes his legendary straight left. This punch went largely unnoticed because of the camera angle and Machida’s blinding speed, but it lands solidly. As proof, Dan was wearing a shiny new contusion under his right eye for the rest of the fight. Notice how Lyoto intercepts Henderson–his left hand connects while Hendo is still in the process of loading up his right– and then immediately takes the angle and puts himself in a position to defend. Dan bullrushed him after this, but to no avail. Blammo! Lyoto takes the H-bomb to the chin, and another one to follow up. I’d like to say that I was impressed with Dan’s quickness on these shots, but at the time I was shitting myself. I was sure that Hendo had just knocked out Lyoto Machida. But the Brazilian ate the punches like Acai and, tying up with ten seconds remaining, sealed the round for good with a beautiful takedown.

Blammo! Lyoto takes the H-bomb to the chin, and another one to follow up. I’d like to say that I was impressed with Dan’s quickness on these shots, but at the time I was shitting myself. I was sure that Hendo had just knocked out Lyoto Machida. But the Brazilian ate the punches like Acai and, tying up with ten seconds remaining, sealed the round for good with a beautiful takedown.

Here we have what I believe is called Chudan Haishu Uke, or a high back hand block. It’s basically a variant of one of the first techniques you would learn as a six year old at a Karate dojo. And wouldn’t you know–the damn thing works! The Machida who used to backpedal away from strikes with his hands down and his chin in the air is no more! Well, he still carries his chin high, true. And yes, he still backpedals an awful lot. But by gum, he blocks when he does it now!

Here we have what I believe is called Chudan Haishu Uke, or a high back hand block. It’s basically a variant of one of the first techniques you would learn as a six year old at a Karate dojo. And wouldn’t you know–the damn thing works! The Machida who used to backpedal away from strikes with his hands down and his chin in the air is no more! Well, he still carries his chin high, true. And yes, he still backpedals an awful lot. But by gum, he blocks when he does it now!

After Santiago, apparently confident in his hips, makes the mistake of switching to wrist control, Nelson drops hard to one knee and drives forward.

After Santiago, apparently confident in his hips, makes the mistake of switching to wrist control, Nelson drops hard to one knee and drives forward. Sensing that Santiago has lost his base, the Scandinavian runs a very short pipe on his foe, circling and dropping the Brazilian to his back.

Sensing that Santiago has lost his base, the Scandinavian runs a very short pipe on his foe, circling and dropping the Brazilian to his back.  And proceeds to smash him with elbows and accurate punches from the top.

And proceeds to smash him with elbows and accurate punches from the top.

Sensing that this might be his meal ticket, Gunni loads up another uppercut. The opening is there, as Santiago leans forward with his back to the cage, chin unprotected.

Sensing that this might be his meal ticket, Gunni loads up another uppercut. The opening is there, as Santiago leans forward with his back to the cage, chin unprotected.

Despite Jorge Santiago’s best efforts, he proves powerless to sway the will of the uncaring Norse gods, and they lead their champion to victory. A last 10-9 round gives Nelson the fight, 29-28.

Despite Jorge Santiago’s best efforts, he proves powerless to sway the will of the uncaring Norse gods, and they lead their champion to victory. A last 10-9 round gives Nelson the fight, 29-28.

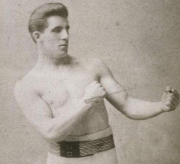

That’s Gentleman Jim Corbett, heavyweight boxing champion, genuine badass, and famed Kenny Florian lookalike. With his “scientific” approach to boxing, he unseated the great heavyweight champ John L. Sullivan and befuddled many larger, stronger opponents with his quick feet and clever defensive style. His stance and hand positioning flies in the face of what modern striking coaches teach their fighters, but Corbett is often credited with being the man who turned the sport of boxing from slugfest to art. And he and the many generations of knowledgeable old-schoolers that came into the sport for generations after him proved that defense has much less to do with hand positioning than it does with posture, footwork, and positioning.

That’s Gentleman Jim Corbett, heavyweight boxing champion, genuine badass, and famed Kenny Florian lookalike. With his “scientific” approach to boxing, he unseated the great heavyweight champ John L. Sullivan and befuddled many larger, stronger opponents with his quick feet and clever defensive style. His stance and hand positioning flies in the face of what modern striking coaches teach their fighters, but Corbett is often credited with being the man who turned the sport of boxing from slugfest to art. And he and the many generations of knowledgeable old-schoolers that came into the sport for generations after him proved that defense has much less to do with hand positioning than it does with posture, footwork, and positioning.